Subsection 3.2.1 A New Notation

"I will always choose a lazy person to do a difficult job…Because (s)he will find an easy way to do it."

Bill Gates

Mathematicians are lazy people. They prefer the easiest or shortest way to solve a problem. Sometimes that involves inventing a new notation. In this lesson we study a new notation called an exponent.

In

Section 1.3 we learned to make a factor tree to write the prime factorization of a whole number. You might review that skill before completing the Warm-Up.

Warm-Up.

Make a factor tree and write the prime factorization of each number:

16 =

32 =

64 =

Did you get tired of writing down all those 2’s?

Each of the factorizations above involves a repeated multiplication. Here is a shorter way to write them.

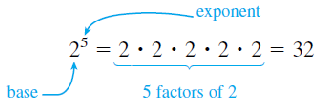

Definition.

An exponent is a number that appears above and to the right of a particular factor. It tells us how many times that factor occurs in the product.

The factor to which the exponent applies is called the base, and the product is called a power of the base.

For example, we can write 32 as \(2^5\text{.}\)

Similarly, we can write

\begin{gather*}

16 = \alert{2^4} = 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2\\

64 = \alert{2^6} = 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2

\end{gather*}

We say that 16 is "the fourth power of 2" or "2 raised to the fourth power" or just "2 to the fourth."

Example 3.2.2.

Use an exponent to write "3 to the fifth power," then evaluate the power.

Solution.

The base is 3 and the exponent is 5. We evaluate the product of 5 factors of 3.

\begin{equation*}

3^5 = 3 \cdot 3 \cdot 3 \cdot 3 \cdot 3 = 243

\end{equation*}

Checkpoint 3.2.4.

Write each power as a repeated multiplication, then evaluate the power. (Use your calculator for part (d).)

\(\displaystyle 6^2\)

\(\displaystyle \left(\dfrac{2}{3}\right)^3\)

\(\displaystyle 10^5\)

\(\displaystyle 1.4^4\)

Answer.

\(\displaystyle 6 \cdot 6 = 36\)

\(\displaystyle \left(\dfrac{2}{3}\right)\left(\dfrac{2}{3}\right)\left(\dfrac{2}{3}\right) = \dfrac{8}{27}\)

\(\displaystyle 10 \cdot 10 \cdot 10 \cdot 10 \cdot 10 = 100,000\)

\(\displaystyle (1.4)(1.4)(1.4)(1.4) = 3.8416\)

A Quick Refresher.

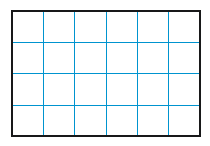

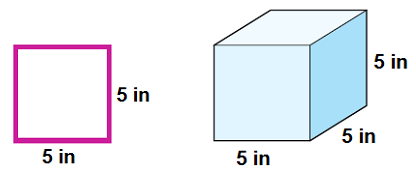

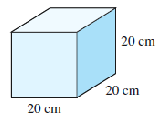

Recall that we can find the area of a rectangle by multiplying its length times its width. In the figures below, the grid lines represent centimeters.

\begin{gather*}

\hphantom{Area = 6 \times 4 = 24}\\

\text{Area} = 6 \times 4 = 24~~ \text{square centimeters}

\end{gather*}

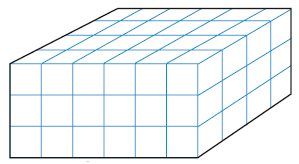

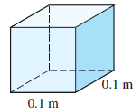

We can find the volume of a box by multiplying its length times its width times its height.

\begin{align*}

\text{Volume} \amp = 6 \times 4 \times 3\\

\amp = 72~~ \text{cubic centimeters}

\end{align*}

Subsection 3.2.3 Products and Powers

How should we simplify the expression

\begin{equation*}

3 \cdot 5^2 ?

\end{equation*}

Should we multiply 3 times 5 and then square the result, or should we square 5 first and then multiply by 3?

Which Comes First?

Which option is correct:

Option 1

\begin{align*}

3 \amp \cdot 5^2 \hphantom{0000000} \blert{\text{Multiply first.}}\\

\amp \rightarrow 15^2 \hphantom{0000} \blert{\text{Then square.}}\\

\amp = 225

\end{align*}

Option 2

\begin{align*}

3 \amp \cdot 5^2 \hphantom{000000000} \blert{\text{Square first.}}\\

\amp \rightarrow 3 \cdot 25 \hphantom{0000} \blert{\text{Then multiply.}}\\

\amp = 75

\end{align*}

We have defined powers so that an exponent applies only to its base, so Option 2 is the correct one.

Powers Before Products.

\(\blert{\text{Rule:}}~~\) Compute powers before multiplications or divisions.

If we really want to multiply before computing the power, we can use parentheses around the product. The parentheses tell us to simplify what’s inside first. Compare the two calculations in the next Example.

Example 3.2.8.

Simplify.

\(\displaystyle 3 \cdot 5^2 = 3 \cdot 25 = 75 \hphantom{0000} ~~\blert{\text{Compute the power first, then multiply.}}\)

\(\displaystyle (3 \cdot 5)^2 = 15^2 = 225 \hphantom{0000} \blert{\text{Multiply inside parentheses first, then compute the power.}}\)

Checkpoint 3.2.9.

\(\displaystyle 5 \cdot 2^3\)

\(\displaystyle (5 \cdot 2)^3\)

Answer.

\(\displaystyle 40\)

\(\displaystyle 1000\)

Subsection 3.2.4 Pythagorean Theorem

Delbert is taking a week-long tour on his trail bike. He is traveling across open country in the West, using a guide book that describes his route and suggests places to camp each night. This morning he read the following instructions in the guide book:

"After breaking camp, ride directly west for 20 miles. You will come to a deep, narrow canyon running north and south. However, there is a dirt road that runs along the east side of the canyon, and precisely where you meet the road there is a bridge over the canyon. Cross the bridge and continue for two more miles to a county park, which is your first rest stop for the day."

Delbert sets out heading west, but his compass is not completely accurate. He is actually riding on a course slightly north of west. When he reaches the canyon, his odometer reads 20.5 miles instead of 20 miles, as the guide book described.

“Oh, well,” thinks Delbert, who is getting a little tired and ready for his rest stop, “That’s not so far off. If I head south on this dirt road I should come to the bridge in just a short distance.”

Warm-Up.

Sketch the situation described in the story. Show Delbert’s camp, the canyon and the bridge, Delbert’s actual route and the route he should have taken.

Without doing any calculations, guess how far Delbert must ride on the dirt road to reach the bridge.

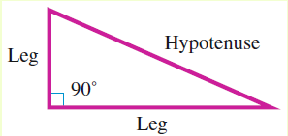

Definition.

A triangle in which one of the angles is a right angle, or 90°, is called a right triangle. The side opposite the right angle is the longest side of the triangle, and is called the hypotenuse. The other two sides of the triangle are called the legs.

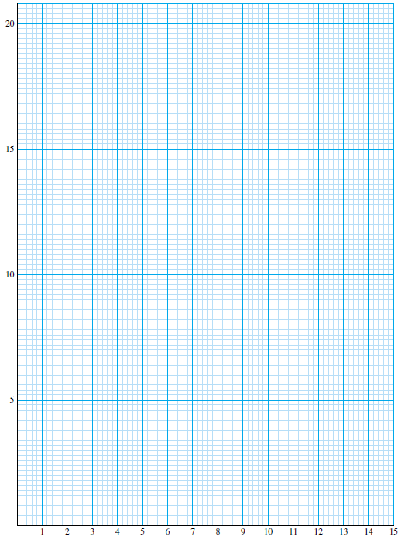

Activity 3.2.2. Pythagorean Theorem.

In this Activity we’ll investigate some properties of right triangles. You will need a piece of graph paper measured in centimeters, similar to the one shown below. Use the grid and follow the steps.

First, measure carefully and cut out a strip of paper or cardboard between 12 and 24 centimeters long. (It will be easier if you choose a whole number value for the length of the strip.)

Use your strip as the hypotenuse of a right triangle on the grid, with the legs on the axes.

Record the lengths of the legs (First Leg, \(FL\text{,}\) and Second Leg, \(SL\)) and the Hypotenuse, \(H\text{,}\) in the first three columns of the table provided. (We’ll get to the other columns in a minute.)

-

Try several different triangles, and record the lengths of the legs.

Table 1

| \(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

| \(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

| \(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

| \(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

Repeat the previous exercise with a hypotenuse strip of a different length, and record your data in the first three columns of the second table.

Table 2

| \(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

| \(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

| \(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

| \(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

-

The last four columns in each table are for recording some calculations. You should be able to interpret what goes in each column:

\((FL)^2\text{:}\) Square the length of the first leg.

\((SL)^2\text{:}\) Square the length of the second leg.

\((FL)^2 + (SL)^2\text{:}\) Add the entries in the previous two columns.

\((H)^2\text{:}\) Square the length of the hypotenuse.

-

Compare the entries in the last two columns of each table. Do you notice any pattern? Summarize your observations as a conjecture

Conjecture:

The Activity revealed a relationship among the sides of a right triangle. If we know the lengths of any two sides of a right triangle, we can find the third side by using a formula called the Pythagorean Theorem.

Pythagorean Theorem.

If the letter \(\alert{c}\) stands for the length of the hypotenuse, and the lengths of the two legs are denoted by \(\alert{a}\) and \(\alert{b}\text{,}\) then

\begin{equation*}

\alert{a^2 + b^2 = c^2}

\end{equation*}

In words, the Pythagorean theorem says:

\begin{equation*}

\blert{\large\text{In a right triangle,}}

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\substack{\hphantom{000}\blert{\LARGE\text{the square of}}\\ \blert{\LARGE\text{the hypotenuse}}}

\hphantom{00000} \blert{\large\text{is equal to}}\hphantom{0000}

\substack{\blert{\LARGE\text{the sum of the squares}} \\ \blert{\LARGE\text{of the two legs}}}

\end{equation*}

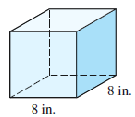

Because the square of its side length gives the area of a square, we can visualize the Pythagorean theorem with areas of squares, like this:

You can check that if we add the areas of the two squares on the legs, we get the area of the square on the hypotenuse!

Activity 3.2.3. Pythagorean Triples.

Whole numbers that fit the Pythagorean theorem are called Pythagorean triples. You can make your own Pythagorean triple by starting with any two whole numbers, which we’ll call \(P\) and \(Q\text{.}\) Fill in the table below by using the rules at the top of each column. The first row is done for you.

| 2 |

1 |

\(2 \ dot 2 \cdot 1 = \blert{4}\) |

\(2^2-1^2 = \blert{3}\) |

\(2^2+1^2= \blert{5}\) |

| 3 |

1 |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

| 3 |

2 |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

| 4 |

1 |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

| 4 |

2 |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

| 4 |

3 |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

| 5 |

1 |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

| 5 |

2 |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

| 5 |

3 |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

| 5 |

4 |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

\(\hphantom{00000}\) |

Which column gives the hypotenuse of the right triangle?

Check that your triples satisfy the Pythagorean theorem.

For this method to work, \(P\) must be greater than \(Q\text{.}\) Do you see why?